Why is it that one should read? Or for that matter, why should one read anything? For starters, I think basic reading is an operational necessity if one needs to function in this world. However, even that isn’t so easy to come by for many.

The 2024 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) suggests that almost one-third of Class 8 students in India can’t read at the expected level. I assume, however, that everyone who can read this article – or who will ever read it – has this basic ability to read.

My quest goes further. It is to understand why do we choose to read something that goes beyond our basic day-to-day functioning?

I think I have found my answer.

The reason I read is because I have this innate curiosity to learn about the world as accurately I can and to understand my place in it. I also read to be conscious. As Jeff Hawkins says, “Consciousness is the moment-to-moment memories of our actions and thoughts”. In a way, then, I read to be alive and to incessantly update my understanding of myself and the world.

Where it began for me

Like most things in life, the genesis of anything meaningful (or traumatic) can be traced back to our childhood. When I look back at my own childhood, I feel that I have always had a love for reading, but it was rather undiscovered.

In India, reading is more about the outcome – performing well on a test or getting through a job – instead of a process of enjoyment, discovery, or curiosity.

I first discovered reading as a process that I loved when I read and re-read Julius Caesar by Shakespeare in Grade 9. That was the first real inclination that I loved reading. But there was hardly any way that I could have built on that inclination. Money was short and mobility was limited. All I could read were school textbooks.

That has changed recently. I have been reading more and more courtesy of the ability to not only buy more books but by having spent days and nights developing my reading muscle. And that has really changed who I am. It has changed how I understand the world and my place in it.

How reading changed my perception of the world

Some of my beliefs have fundamentally changed. Here are a few examples –

| Earlier belief (when I would believe what was told to me) | Current Understanding (based on what I have read) |

| You are born with talent. It’s in your genes or not. | Talent can be developed. Everything and anything can be learned. |

| We (humans) are created by someone called God out of thin air. | Humans are the result of billions of years of evolution and have emerged from a single-celled organism. |

| My moral choices will decide if I go to hell or heaven. Ex: Attraction towards opposite sex is morally wrong and you should feel ashamed of yourself. | There is no hell or heaven. Attraction towards opposite sex is part of who we are as human species. That’s how we propagate our genes. |

| Money could very well define the true meaning of happiness. | Money is important, but only a part of the true meaning of happiness |

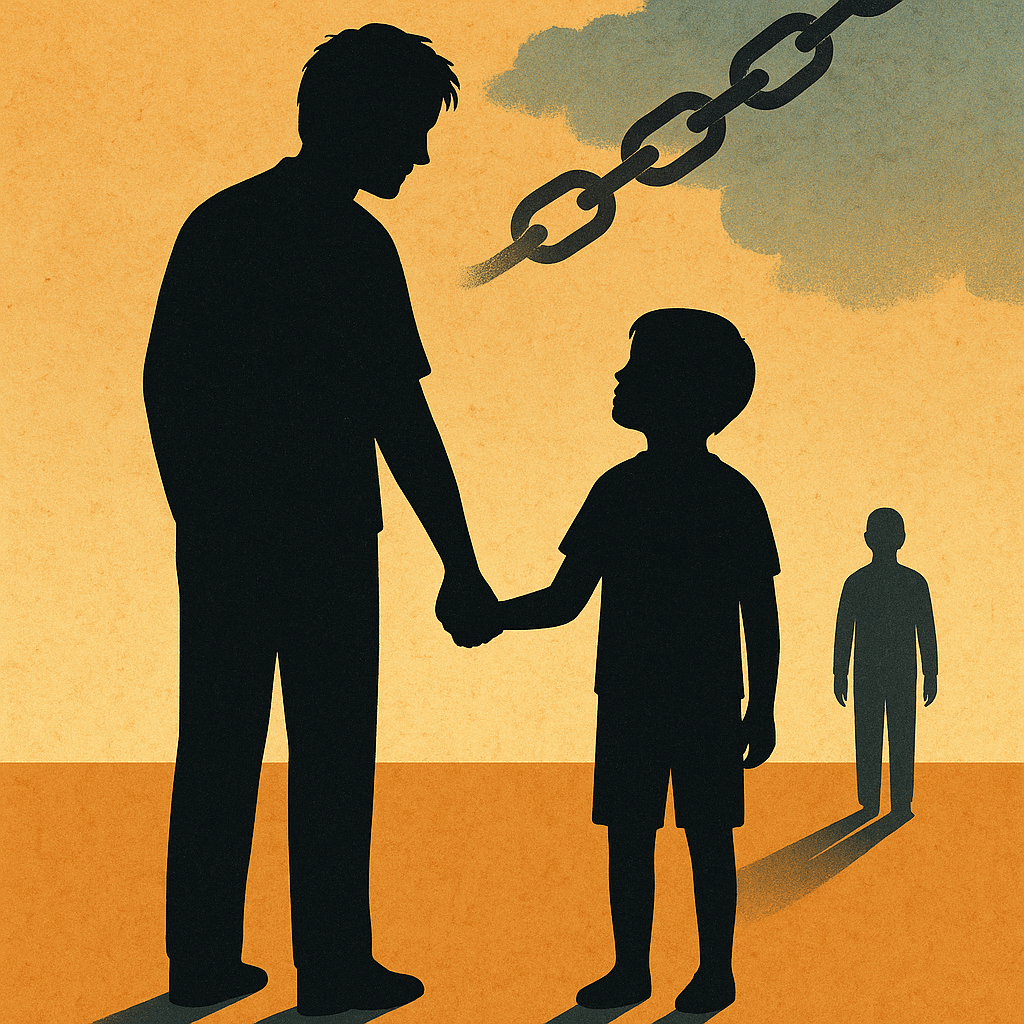

| You always need to listen to your parents/elders because they are always right. | Your parents/elders are humans too – and they are wrong many times. You have to learn how to outgrow them. |

| Your first instinct about something is usually right since it is coming from your gut. | Your first instinct is mostly wrong as it depends on your old brain, which is driven by survival. |

| Eating sugar as much as you can is okay. | Eating sugar has many negative consequences and is largely a function of the old brain wanting to gather as many calories as possible |

There are many such examples that I can think of. The point is I would never have updated my earlier beliefs had I not read as much as I had over the last few years and applied those learnings in my life.

One may ask what’s the point of all this anyway? My current understanding can still be proven wrong. That’s where what one reads becomes important. My criteria –

- I read books that have stood the test of times or what we call are the classics, especially when it comes to topics like philosophy or religion.

- I read books written in simple language that explain peer-reviewed scientific concepts. I am not a scientist, so I often seek help – especially from my wife, who is a scientist – to check the understanding I gain from these books.

Reading in 2025

The year 2025 was a decent year for me in terms of what I read and how much I read. I am limiting this article only to full-length books and not including newspapers or online articles.

In total, I read 28 books, which comes out to roughly 2.5 books a month. I would have liked to read more, but this is the best I could do.

THE BOOKS I READ (In order)

- Brave New Words, Sal Khan.

- The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, Eric Jorgenson.

- Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari.

- Lifespan, David Sinclair.

- The Disciplined Mind, Howard Gardner.

- Changing Minds, Howard Gardner.

- How Economics Explain the World, Andrew Leigh.

- As Gods Among Men, Guido Alfani.

- Mindset, Carol Dweck.

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack, Charlie Munger (half)

- Origin Story, David Christian (half)

- Brave New World, Aldous Huxley.

- Kafka on the Shore, Haruki Murakami.

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerers’ Stone, J.K. Rowling.

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, J.K. Rowling.

- The Good Life, Marc S. Schulz and Robert J. Waldinger.

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, J.K. Rowling.

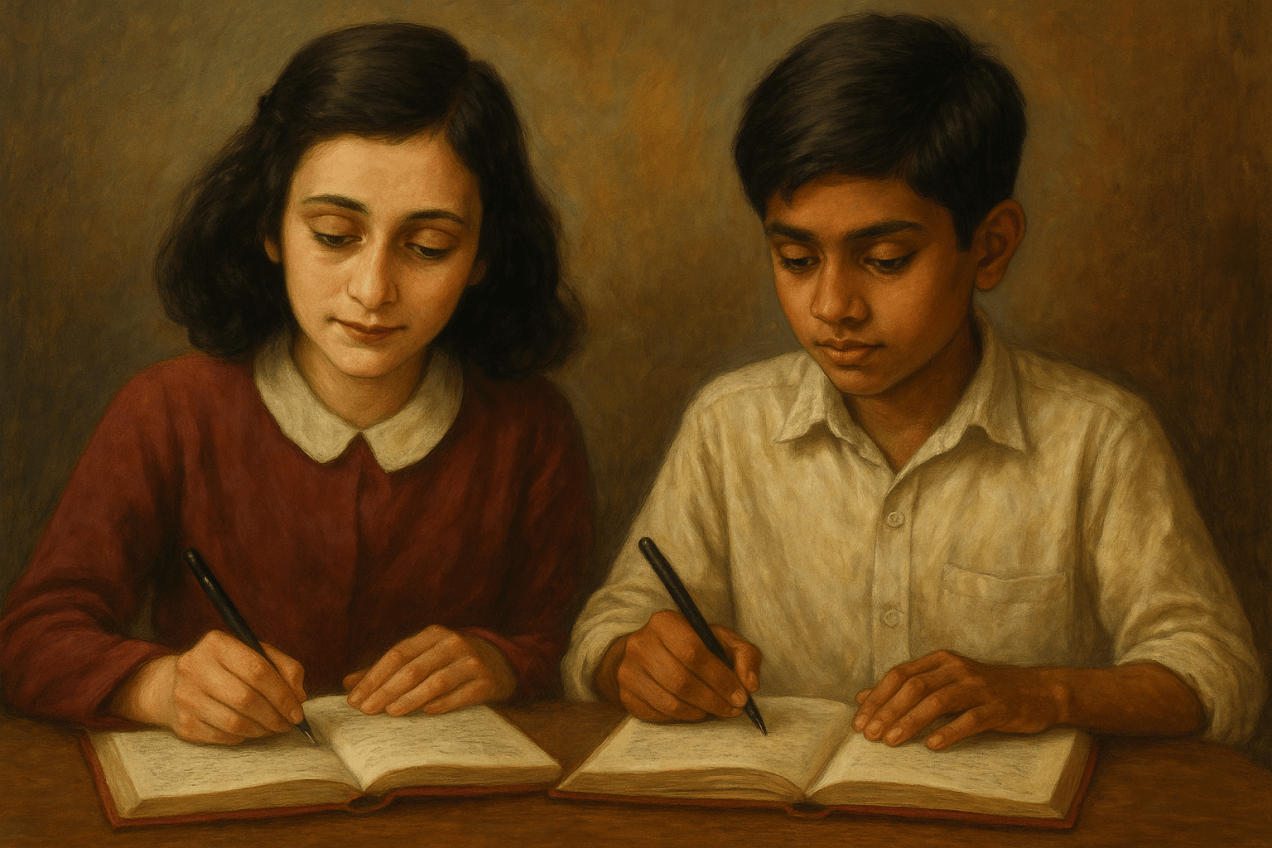

- The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank.

- The Happiness Files, Arthur Brooks.

- The Price of Our Values, Augustin Landier and David Thesmar.

- Career and Family, Claudia Goldin.

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, J.K. Rowling.

- How the World Really Works, Vaclav Smil.

- The Coming Wave, Michael Bhaskar and Mustafa Suleyman.

- The Journey Home, Radhanath Swami.

- Numbers Don’t Lie, Vaclav Smil.

- A Thousand Brains Theory, Jeff Hawkins.

- Sri Aurobindo and the Mother on Education

Patterns that emerged

Interestingly, as I look back, there emerged a pattern from what I read –

- The Future of AI and humans:

I inherently got curious about AI and where it is going. I started the year with Sal Khan’s ‘Brave New Words’ which talks about how education will evolve with the coming AI revolution and ended up with Mustafa Suleyman’s, ‘The Coming Wave’ and Jeff Hawkins,’ ‘A Thousand Brains Theory’.

Reading them makes me convinced that AI is NOT becoming more intelligent than humans in totality for many years to come. Yes, it will do some tasks much better than us but becoming better than humans in ALL tasks at once is probably a far-fetched dream. - My childhood Wish List:

As a young kid, I wanted to read the Harry Potter books but never had the chance. I also tried to read Anne Frank’s diary about her time spent in hiding during the World War 2 (read my post on her book) but found it too difficult to read. This year, I managed to finish four Harry Potter books and the famous diary. - Understanding the World through Economics and Practicality:

The book that made the greatest influence in this category has to be the one by Claudia Goldin called “Career and Family”. It’s the book that got her the Nobel Prize in Economics. The central idea of the book that in today’s world where women wants both career and family, couple equity matters.

Another one is “How the World really works” by Vaclav Smil in which he says that despite what anyone says, the world will keep running on fossil fuels for many more years to come. Did you know that almost 83% of all our primary energy needs is still driven by fossil fuels? It was almost similar a couple of decades back too. - Understanding Happiness:

Since childhood, I always wanted to understand happiness. I have always believed that happiness is not driven by money or accomplishments alone. Rather it is a driven by good relationships.

This belief was validated by Schulz and Waldinger’s book, ‘The Good Life’, which has to be the best book I read this year since it gives solid evidence by the virtue of being the longest study on happiness spanning more than 85 years.

Some of what they said was also echoed by Arthur Brooks in his book ‘The Happiness Files’ but if I have to choose one, I will go with The Good Life. - Books on education:

Being an educationist, this category had to be there. But honestly none of the books I read this year gave me something new.

If I had to recommend my top three books of the year that everyone must read:

- The Good Life

- The Diary of a Young Girl

- How the World Really Works

Add-on: Brave New World (a classic)

I don’t know what the next year will bring when it comes to reading, but I am hopeful that I read more than I did this year – and that I come closer than I am today to better understand this world and myself.

Any recommendations on what should I read in 2026?

REFERENCES

Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024, Pratham Education Foundation

https://www.asercentre.org/aser-2024