One sunny afternoon, as my wife was working on one of her academic papers, she told me she had been feeling fearful — of the writing process, and of the feedback she might receive from her guide and the scientific community. When I asked why she felt this way despite being well prepared, she admitted that, even now, she sometimes experiences the same fears she had as a child. It wasn’t failure she was afraid of, but the possibility of not producing a paper that was perfect.

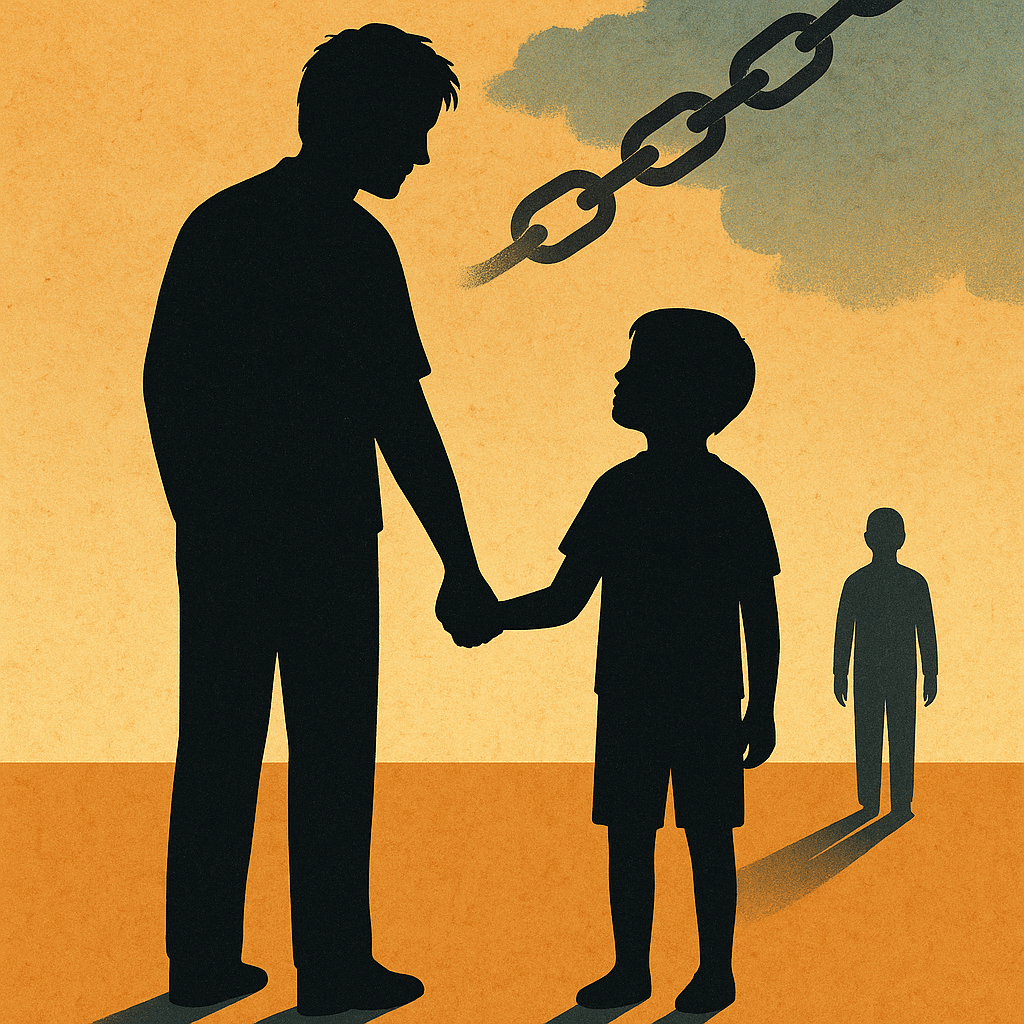

Many of the fears we carry into adulthood are not entirely our own. They are echoes — internalized through childhood experiences, social environments, and often, the unspoken anxieties of those who raised us. Psychological research shows that fear responses are not purely innate; they are also socially learned and transmitted across generations (Gerull & Rapee, 2002).

Her story reflects this truth: fears from childhood often remain embedded in adulthood and if not acted upon can be traversed to our next generation i.e. our kids.

These fears can emerge from multiple sources –

- Direct and deep personal experiences (e.g., repeated punishment, ridicule) as a child;

- Socio-economic circumstances (e.g., scarcity, instability);

- Educational environment (e.g., high-stakes grading, unsupportive teachers);

One of the most common ways children internalize fears is through parental modeling — observing and adopting their parents’ anxieties. I will focus primarily on this aspect in this piece.

This is part of a writing series I am calling “Notes to my child” where I am trying to document my thoughts and strategies of raising my future kids and sharing these with my co-travelers.

Positive vs Negative Fear

Let me also clarify that no parents actively try to make their children fearful or pick up their anxieties. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. Both as current or future parents, it’s important that we raise our children without unnecessary fear. This is harder to do than it sounds.

Positive fear is necessary. It helps a child survive in this world. It ensures that they don’t poke their fingers inside the electric switch board or stand, smiling, in front of a pouncing lion.

While positive fear can be considered as a “built-in alarm system”, the negative fear is a “built-out, overactive alarm system”. It goes off even when there’s no real danger.

| Negative Fear | Positive Fear | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Control-oriented, performance-pressured, or socially conditioned | Protective, survival-oriented |

| Effect | Limits growth, creativity, and willingness to take healthy risks | Keeps us safe from real, immediate danger |

| Examples | Fear of making mistakes in public Fear of being judged or criticized Fear of trying something new unless it’s “perfect” | Fear of touching a live electrical wire Fear of walking too close to the edge of a cliff Fear of running into a lion |

| Outcome | Can lead to procrastination, avoidance, and low confidence. It often lingers long after the actual risk has passed. | Helps avoid physical harm or serious risk. Once the danger is gone, the fear subsides. |

A Thought Experiment: Three Parenting Advice

How does this negative fear get transferred from parents to children then?

Let’s try to understand this with the help of a thought experiment:

Imagine a ten-year old child who has been asked to speak in a school assembly on the topic of “cleanliness”. The child comes home and tell this to his parents. The parents help prepare him a paragraph on the topic and asks him to practice.

Imagine this child being raised by three different set of parents: Parents 1, 2, and 3. Each set of parent gives different set of instructions and/or set different expectations for their child.

Parent 1: “You have to make sure that you remember everything by heart and don’t forget anything while you speak. It has to be perfect and according to what we taught you. Remember practice makes a man perfect! The way you perform in pressure situations will indicate how well you will do later in similar situations in life.”

Parent 2: “It’s good that you remember everything and we hope that you will be able to speak what you have prepared. It might happen that you forget a few things while on stage but you should remember the overall message on cleanliness that you want to convey! Good luck!”

Parent 3: “We don’t think that you need to prepare anything for such a simple topic or that you need any help from us. Just go and speak what you think comes to your mind. Just remember to not say anything stupid. Anyway, we don’t have much time to give.”

Now, the next day, the child performance, on a parameter of 100% perfection was, lets say, 80%. He forgets something during their speech but manage to put up with the task. How do you imagine Parent 1, 2 and 3 to react? I believe it will be something like this –

Parent 1: “You forgot the last line we practiced! We told you exactly how to say it. You need to prepare more seriously next time — mistakes like this can be avoided.”

I will call this type of response as a “Perfection-Driven Response. Research says that, for example, “fathers of high socially anxious children exhibited more controlling behaviors. (Flett et al., 2002).”

Parent 2:

“You spoke well! You missed a few points, but you got the message across — that’s what matters. Next time, you can add those points too.”

I will call this type of response as a “Encouragement-Centered Response.” Research says that Growth-oriented feedback fosters resilience and intrinsic motivation. Carol Dweck’s work in this regard is path-breaking where she speaks on growth vs fixed mindset.

Parent 3:

“At least you didn’t embarrass yourself. See? It wasn’t that big a deal.”

I will call this type of response as a “Hands-Off Response.” Research says that emotional neglect or low parental engagement can reduce self-efficacy and ambition.

What do you think were the child’s takeaways from each parent’s responses and how these takeaways would echo in children’s adult life?

Here’s my take –

| Parent Reactions | Child’s Takeaway | Adult echo |

|---|---|---|

| Perfection-Driven | My value depends on meeting the exact expectations set for me. If I miss a detail, I’ve failed in the eyes of my parents. The society must also consider me a failure because my parents think so too. I must avoid mistakes at all costs. | I can’t start unless I’m sure it will be perfect. Any imperfection is a failure. |

| Encouragement-Centered | Mistakes happen, but they don’t erase the value of what I’ve done. My job is to convey the essence, even if it’s not perfect. The society must be more willing to accept my mistakes in the future which helps me in taking more risks in life. | I can try things even if they’re not perfect. Progress matters more than perfection. |

| Hands-Off | What I do isn’t important enough for support. As long as I avoid humiliation, it’s fine. The society doesn’t care much what I do or not do. As long as I don’t come out as stupid, it should be fine. | Why bother striving? Just avoid looking bad and get it over with. |

Breaking the Cycle

Objectively speaking, each child received same results. But it received different reactions by parents resulting into starkly different takeaways by the child. These takeaways, and many such similar experiences through parental interactions, starts to define a child’s personality including their anxieties and fears.

Breaking this cycle of inherited fear requires conscious, consistent effort as an adult. This becomes even more critical if as parents we want our children to lead lives without any kind of negative fears.

Some strategies include (but not limited to):

- Self-Awareness First – As adults, we should start by identifying our own learned fears before addressing them with children. Activities such as reflective journaling, therapy, and mindfulness can help uncover inherited anxiety patterns.

- Modeling Self-Compassion – Most of the time, adults are too hard on themselves and they forget to treat themselves with self-compassion. It’s important that adults treat both their and children’s errors as learning opportunities rather than proof of inadequacy. Modeling self-compassion in front of children reduces their fear of failure.

- Encourage Process Over Perfection – Praise effort, strategies, and persistence instead of flawless outcomes.

- Provide Emotional Safety – Create environments where children feel safe to try, fail, and try again without ridicule or disproportionate punishment.

- Educate on Fear Itself – Teach children the biological purpose of fear and how to distinguish between positive fear (real danger) and negative fear (false alarms).

We can’t shield children from all fear — nor should we. But we can prevent unnecessary fears from taking root. That means being mindful of the lessons we give, both in words and in the silences between them. By practicing these habits, we reduce the risk of passing on our own fears and anxieties — giving children the space to develop confidence, adaptability, and a healthy relationship with imperfection.

Whenever my wife finally submits her paper, I hope that she smiles and says, ‘It’s not perfect — but it’s done.’ The courage she will learn is the courage that I’d want our children to inherit.

References

Gerull, F. C., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Mother knows best: Effects of maternal modeling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behaviour in toddlers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00013-4

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Oliver, J. M., & Macdonald, S. (2002). Perfectionism in children and their parents: Associations with depression, anxiety, and everyday distress. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020779000183

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.