The Question of Purpose

Purpose is such an intriguing word. Why do we choose to do the things we do in life? My dearest friend who dreams of becoming a filmmaker recently asked why he should bother pursuing anything worthwhile—or even something he loves—when, in the end, we all have to die?

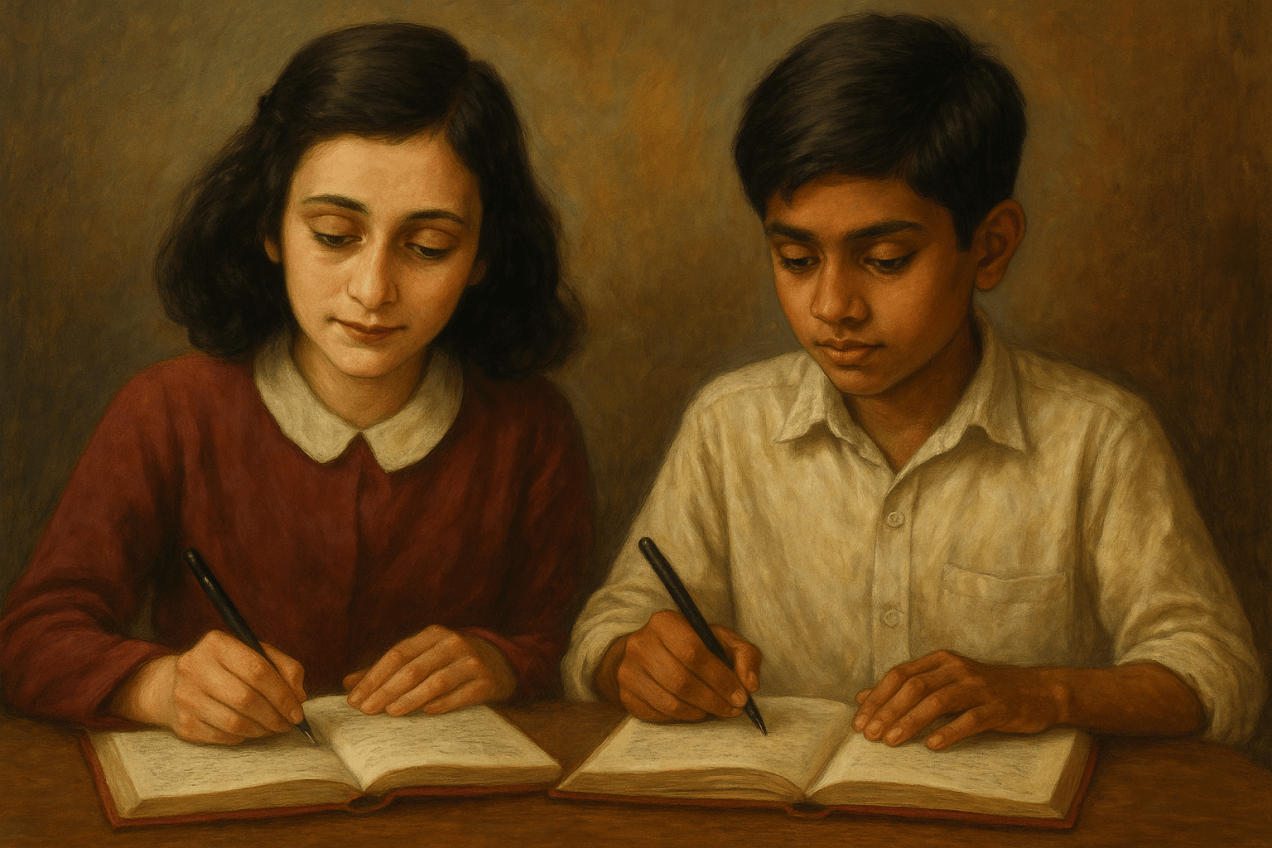

It’s a profound question, one without a single, simple answer. Yet, few stories and moments often help us glimpse possible responses. For me, one such answer revealed itself in the pages of Anne Frank’s diary, written by a young Jewish girl who perished in the Holocaust during World War II.

Meeting Anne for the First Time

Called The Diary of a Young Girl, I first came across this book when I was just starting to explore the world of reading as a young eighteen-year-old. I remember trying to read it then, but as the saying goes, “you don’t choose your books; they choose you”— and in that moment, the book had decided to reject me.

I don’t know why I felt compelled to return to this book at this moment in my life. The thought about my life’s purpose shouldn’t be the cause because I do feel certain of it—to improve the lives of millions of underprivileged children in India—and yet, I still found myself drawn back to these pages.

Maybe it was a quiet intuition, or perhaps a kind of divine signal, that led me to it. I simply felt drawn to discover what this young girl of thirteen had written in those 330-odd pages before she and her family were taken from their hidden refuge and sent to the concentration camps. This time, the book let me in. And it has already changed my life.

Finding Myself in Anne’s Writings

Reading Anne’s diary made me think back about the time I had started to write my own diary (later discontinued) when I was in Grade 7 or 8—around the same age as Anne. Of course, in hindsight, what I was going through as a twelve-year-old was in no way close to what Anne endured. She was hiding from the Nazis inside a secret annexe in the middle of a war, unable to step outside, while I was simply navigating the small-er dramas of adolescence. But as a teenager, “your” challenges feel most important to you.

Perspective-taking and empathy takes time. Evidence from child psychology hints that empathy and perspective-taking continue to develop into the teenage years, with notable patterns emerging especially during the late adolescent period.

A six-year longitudinal study following adolescents from ages 13 to 18 found that perspective-taking increased consistently across adolescence, indicating that the ability to adopt others’ viewpoints develops substantially during the teenage years and continues to strengthen into late adolescence (Van der Graaff et al., 2013).

While perspective-taking shows steady growth, empathy itself follows a more complex developmental path.

A study summarized by Melbourne Child Psychology reported that cognitive empathy—the capacity to understand another’s perspective—emerges earlier for girls, beginning around age 13, while boys typically do not show similar growth until about age 15. By contrast, affective empathy, which reflects the emotional responsiveness to others, tends to dip in boys between ages 13 and 16 before rebounding later in adolescence, suggesting a temporary decline followed by recovery in emotional empathy during the teenage years (Melbourne Child Psychology, n.d.).

The beauty of Anne’s diary is that you can actually witness this growth many years before this research was contemporary. Between the ages of thirteen and fifteen, her writing reflects a deepening perspective and a widening empathy—especially in the way her relationship with her mother evolves. She begins with sharp criticism, often feeling misunderstood, but over time her words soften, carrying traces of compassion and self-awareness.

Shared Struggles of Adolescence

In Anne’s struggles, and growth, I found echoes of my own teenage self. Like Anne, I too wrestled with the urge to be independent—“please let me be… leave me alone!” I felt the need to push away adults—“I am my own person… don’t tell me what to do!” I carried confusing feelings about the opposite gender—“What is this feeling… am I in love?” And I wanted nothing more than to be seen as honest—“Don’t ever tell me that I lie…”

There were other areas of resonance too: Anne didn’t like Algebra, neither did I. Anne loved reading and thinking deeply about human emotions—so did I. Anne wanted to become a writer or a journalist—so did I. And despite the Nazis’ annihilation of the Jews, Anne believed in the good in people. So did I.

The Power of Expression

But there was more than resonance that made Anne’s life special and why she was different than everyone her age (and beyond) those days and today. She was special because she chose to give value to how she was feeling—and to express it with what she had in that moment. For her, that meant words. Unknowingly, she had found a purpose. And that made her immortal.

The most wonderful thing about reading her diary is that you don’t feel that she was writing for the world. Living a double life —on one side she could be caught at any moment, and on the other she might survive the war—she still kept on writing for herself. She wrote to understand herself, to become better.

And that’s what makes her lesson so powerful. As individuals, what we go through every day often seems too ordinary. It doesn’t feel important. We convince ourselves that in the noise of the world, our feelings and stories don’t matter. For the longest time—maybe even for our entire lives—we ask: who will hear what we have to say?

The fact that Anne must have felt this too, but still chose to express, is what makes her life and her story so extraordinary.

Time: Endless and Fleeting

There isn’t much time left. There is a lot of time left. Which statement do you think is true? Believing that we may die in the next moment—courtesy of life’s unpredictability—the first feels true. Believing that we have years ahead, the second feels true as well. The fact is that both statements are true at the same time.

The double-truths resemble Schrödinger’s cat—the famous thought experiment where a cat could be considered both alive and dead at the same time

As humans, we know deep down that our lives are totally unpredictable. We can go poof anytime. Still, we go on thinking that we have an “entire” life in front of us—until it is not. And when we believe our lives to be eternal, we postpone expressing our deepest feelings. We forget to tell others—and, most importantly, ourselves—what we truly think.

The Choice to Express

And yet, Anne did not forget or postpone. She wrote. She expressed. Even in the confines of an attic, even in the face of constant fear, she chose to give her feelings a voice. And through that simple, honest act, she continues to live.

That, to me, is Anne’s greatest gift: a reminder that expression itself can be purpose. It doesn’t have to be grand, it doesn’t have to be meant for the world—it just has to be true.

So, just like Anne, we too must continue to express, in whatever way we can. For some, that might mean writing; for others, it could be painting, singing, filming (my friend), teaching, or even simply speaking honestly to a friend. Expression doesn’t have to be grand—it just has to be true.

For me, that means writing more, and making space for my thoughts to breathe on paper (and online). It has now become not just an act, but an added purpose of my life. And perhaps, in doing so, I will leave behind a small echo—one that says: I too lived, I too expressed.

So let me ask you—when your time comes, will the world know that you lived, because you expressed?